Gregory Bateson once wrote, humans think in stories. But what if it goes deeper than that? What if we are stories? What would it mean to be a story? In order to answer that question, we first need to be clear about what a story is.

One of the definitions we might have been taught in school is that a story is a connected sequence of events. That makes it sound like you could throw any group of events together and call it a story. But that is not true.

What most people don’t get taught in school (at least I didn’t) is that it is the structure of the connections in a story that creates the meaning. In muc the same way, a sentence is a connected sequence of words, but it is the grammar that creates the meaning. If we want to know what a story is, we need to understand its grammar. To use another idea from Gregory Bateson, we need to look for the pattern that connects.

Fortunately, much of the work of identifying the grammar of stories has already been done for us. That grammar appears to be a universal pattern that exists across all cultures, as attested by the fact that Joseph Campbell discovered it by conducting an extensive analysis of mythology from across cultures in his brilliant book The Hero With a Thousand Faces.

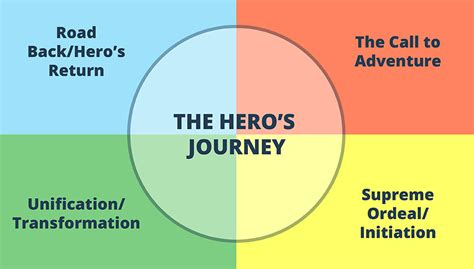

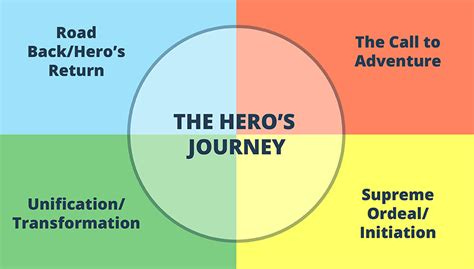

Since Campbell’s work, further analysis has been conducted detailing the technical structure of the hero’s journey down to a very fine level of detail. At the broadest level, though, we can define the pattern which Campbell discovered as a cycle-ending-in-transcendence. What this means is that the hero returns to the same status that they began the story in but have qualitatively changed as a result of their journey.

Campbell was strongly influenced by the work of psychologist Carl Jung, and so it’s no surprise that he used a psychological lens with which to view the cycle-ending-in-transcendence. For him, the hero begins the story in a state of consciousness. They are in a world that they understand; a state of equilibrium. They will receive a call to adventure which invites them into a world that they do not understand. This is a descent into the unconscious. The resoluton of the story is a return to understanding and consciousness. Because the start and end state are the same, we can see that the pattern is a cycle.

The transcendence part of the equation comes from the fact that the hero has returned with something. The hero has won a prize from the unconscious and incorporated it into consciousness.

Let’s think of a really mundane example of this pattern of a cycle-ending-in-transcendence.

You’re driving in your car and everything is going fine. You are in a state of consciousness in a world that you understand. The car breaks down. That’s the call to adventure. You don’t know much about how cars work and so you don’t know what the problem is. You are now in an unconscious state i.e. a world you don’t understand. You organise a towtruck to transport the car to a mechanic who tells you what is wrong and fixes the problem. Now your car is up and running again and you’re back to a world that you understand. But you’re now aware of a new failure state for your car and probably how to try and avoid it in the future. That new piece of knowledge is the prize you won from your journey; your transcendence.

Stories can range all the way from such everyday banal occurences up to life-altering and even civilisation-altering events. The magnitude may change, but the pattern remains the same.

Now, we have said that Campbell was influenced by Jung and that’s why his analysis was first and foremost psychological in nature. The psychological lens is a crucial part of the pattern. But there is another aspect that we need to consider and it was described by another great comparative scholar several decades before Campbell.

The scholar in question was the anthropologist, Arnold van Gennep. In his classic work, The Rites of Passage, van Gennep outlined a pattern that was identical to Campbell’s. Just like Campbell, van Gennep based his analysis on an extensive cross-cultural analysis of ceremonies and rituals.

Now, we might ask the question: what is the difference between a story and a ritual? Rituals are made up of highly formalised action. You have to be in a certain place at a certain time. There’s an etiquette to attend to. You have to wear clothing suitable for the ocassion. You have a certain role to play that has fixed behavioural expectations associated with it. In short, ritual requires action.

This is not really true of stories. You can argue that the telling, hearing or reading of a story is an action. That is technically true. But there are no behavaioural expectations associated with the telling or receiving of a story unless the story is told in what is already a ritual and ceremonial fashion in which case the telling of the story is itself a rite of passage.

In essence, stories are intangible and inward-oriented while ceremonies and rites are tangible and outward-oriented. We call the former esoteric and the latter exoteric. The reason why the psychological lens works so well for stories is because they are esoteric in nature. That’s why Campbell was able to use the Jungian framework so elegantly in his analysis of the hero’s journey.

Van Gennep, however, was an anthropologist concerned with the external forms of human society. The meaning of a rite of passage is conveyed by the actions that are carried out. That is why we can say that they are exoteric in nature.

Similarly, we can say that the outcome of a rite of passage is exoteric. A story is a connected sequence of events leading to a psychological transcendence for the hero. A rite of passage, on the other hand, leads to a transcendence that is primarily socio-cultural. Rites of passage function as cultural markers of exoteric transitions. They are the means by which society formally recognises important state changes among members of the group.

Let’s take the car example again. If you decide you want to become a mechanic, there a process to go through. That process is a rite of passage. You begin the rite of passage as an apprentice and you end as a fully-qualified mechanic. There may be formal ceremonies to mark that ocassion or at least letters of recognition from offical bodies. In any case, society now recognises you as a mechanic.

It is this exoteric, socio-cultural focus of the anthropologist van Gennep which balances the psychological perspective of Campbell. These are not mutually exclusive viewpoints. They are, in fact, two sides of the same coin. Every hero’s journey is a rite of passage and vice versa.

We can see this from the fact that most cultures combines myths and stories with rites of passage. The initiate in a hunter-gatherer tribe is told that he is following in the footsteps of the timeless heroes of the culture. He knows about them because he is long familiar with the stories of their deeds. Similarly, the member of a Christian congregation receiving the eucharist understands the meaning of the rite based on the story of Jesus. The story and the rite reinforce each other. It is for this reason that they have the same underlying structure: the cycle-ending-in-transcendence.

Let’s now use an example from film to elucidate the esoteric and exoteric aspects of the cycle-ending-in-transcendence.

Almost everybody would be familiar with the story of the first three Star Wars movies. Luke Skywalker is the hero. Accordingly, it is his cycle-ending-in-transcendence which forms the backbone of the plot, although, like any good story, the other main characters all have their own hero’s journeys as well.

The way the story evolves over the first three movies, we see that Skywalker is going through a rite of passage. He’s not doing an apprenticeship in fixing cars, but rather is being initiated into a sacred metaphysics known as the Force. Just a like an apprentice mechanic, however, he needs somebody to teach him, and that role falls to the Elder character Obi-wan in the first movie and then Yoda in movies two and three.

This is an anthropologically accurate way to depict initiation. Every rite of passage is led by one or more Elders. That is true in a hunter-gatherer initiation rite, in the education given to a young Spartan warrior, and in a mechanic apprenticeship. The details of the rites of passage are different, but the underlying pattern remains the same.

A big part of the drama in Star Wars comes from the fact that Skywalker has two very different initiations to choose from. Remember that rites of passage always have a social, cultural, and political aspect. To be initiated is to be inducted into a sociocultural system. Skywalker has a choice between joining the rebels or joining the empire. Darth Vader and Palpatine are the Elders offering him initiation into the socio-political institution of the empire, while Obi-wan and Yoda are the Elders offering initiation into the socio-political system of the rebels.

What is common to both, however, is the role that Skywalker will attain. At the end of the third movie, he has become a Jedi. That is a title recognised by the society in which he lives in just the same way that our society recognises the titles of priest, doctor, professor, judge and mechanic.

From an exoteric, socio-cultural point of view, Skywalker transcends to the recognised role of Jedi at the end of the story. We know, because the movie shows us in great detail, that he has also overcome all of the psychological challenges required for the esoteric transcendence that Campbell had in mind with his analysis of the hero’s journey. Thus, the exoteric and esoteric dimensions of Skywalker’s journey are in balance. His transcendence is both spiritual and psychological, as well as social, cultural, and political.

In an ideal world, the exoteric and esoteric dimensions of our lives are in alignment. However, they may get out of balance. Where the exoteric exists without the esoteric, we have the empty ceremony that bestows honours and titles on people who have not overcome a corresponding inner challenge. We can think of that as a rite of passage without a hero’s journey; a societal transcendence without a psychological one.

Where an esoteric challenge has been overcome but is not recognised by society, we have a hero whose transcendence is not recognised. Sometimes, a society may actively persecute the hero. That gives us the apostate or heretic.

Imagine an alternative conclusion to Return of the Jedi where Luke Skywalker has successfully become a Jedi but where the empire defeats the rebels. If Skywalker somehow survived, his esoteric achievements would not be recognised and he would no doubt become a marked man.

We can start to see why the social, cultural and political dimension to the cycle-ending-in-transcendence cannot be ignored and why we need to incorporate van Gennep’s exoteric perspective alongside Campbell’s psychological one.

However, at a more general level, rites of passage and hero’s journeys are both ways in which individuals are inducted into their society and culture. Star Wars makes such a useful case study in this respect because Luke Skywalker has a choice between two very different societies and two very different cultures. Most of us never get such a choice, at least we are not conscious of having one.

When we understand that stories are initiatory devices, we can see that the heroes of a culture reveal something about it. It is no accident that Star Wars is one of the most popular films in American history because Luke Skywalker is a very American hero. His choice between rebellion and empire is the same choice made by the colonists who fought the War of Independence. Star Wars is in many respects a re-telling of the foundational myth of the USA.

The stories a society tells itself and the rites of passage that it creates are the ways in which culture is transmitted to the next generation. The magic of stories is that we share in the transcendence of the hero. The cycle-ending-in-transcendence operates on us too. That is what is at stake with stories, and that is why we should give them the reverence which is their due.

Hi Simon,

Here goes: <a href="https://charleseisenstein.substack.com/p/the-sith-a-political-allegory">The Sith: A political allegory</a>

I'll be very interested to hear what you've got to say about the essay.

Cheers

Chris

Hi Simon,

We like to think in stories as well, and in my line of work, it's often easier to explain a complicated abstract notion when the explanation is presented in the form of a story. People take that in far more quickly than a simple abstract explanation of an abstract notion. Stories are powerful.

A few weeks, or maybe even a month ago I read an amusing defence of the Sith Lords and their take on the whole Star Wars transcendence of the hero. It was interesting to flip the story on it's head. Did you see that?

Cheers

Chris